Cash Cow Nixon

In a golden age of corruption, the milk industry was cream of the crop

By Forrest J.H.

The White House was far beyond the tipping point in March of 1971.

The election year was fast approaching, President Richard Nixon's Watergate conspirators set out to sabotage their enemies, American war criminals were earning convictions for their atrocities in Vietnam, and lobbyists for Big Milk had sown the seeds for an important opportunity.

Led by powerful industry group Associated Milk Producers, Inc., a handful of cunning political navigators secured big gains for themselves in an era of rampant corruption. It was a plan years in the making. The secret agreements, bags of cash, double-crossing, ghost organizations and shamelessly illegal scheming would all come to light later; after the milk lobby secured over $100 million in price assurances in exchange for a comparatively small investment in President Nixon's re-election slush fund.

"Better get a glass of milk," quipped White House Counsel John Ehrlichman to the milk industry bosses chumming it up with Nixon in the Oval Office. "Drink it while it's cheap."

THE LEAGUE OF INVOLVED CITIZENS

The world teetered on a conflict that would guarantee at least 70 million American deaths, Nixon thought.

"Whoever is President of the United States, and what he does, is going to determine the kind of world we have," Nixon told author Allen Drury. "I don't think that kind of national suicide is feasible any longer, for any sane man."

A bribe from supposedly trustworthy American milk industry representatives probably just did not seem like a big deal - or even unusual - compared to what was on Nixon's mind.

It wouldn't have seemed like a big deal to those pitching it either, since they had made a common practice of doling out big campaign contributions to their chosen winners, Republicans and Democrats alike.

They designed a system to evade detection. If they had contributed more than $3,000 at a time, they would have owed gift taxes. So they broke up millions of dollars into $2,500 installments to be distributed through shell entities, clouding the money's origin. Those checking campaign finance disclosure forms would have seen these contributions flowing to campaigns by way of benevolent-sounding organizations like Citizens for a Better Government, or Americans United for Sensible Politics, or the League of Involved Citizens.

Treasury Secretary John Connally felt like he was pulling the strings.

"Look here," Connally said to Nixon in the Oval Office on March 23, 1971. "If you have no objection, I'm going to tell them they've got to put so much money directly at your disposal."

Transcripts of this conversation were held by the National Archives for more than 20 years after Nixon left office, and several more years after he died.

"They're committed to $90,000 a month," said White House Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman.

It wasn't enough.

"[Connally] knows them well and he's used to shaking them down. Maybe he can shake them for a little more," Nixon said. "You see what I mean?"

It seems awfully brazen, but the milk industry's payouts were an open secret in Washington D.C., one Nixon had known about for a long time.

EVERY LAWYER AND CONSULTANT IN WASHINGTON

The milk lobby's big push for influence at the White House began in 1968 with then-president Lyndon B. Johnson and Vice President Hubert Humphrey. In the first few months of the year, the Associated Milk Producers, Inc. had illegally spent over $150,000 for Johnson's favor. Just before the Democratic primary election in Wisconsin, where the milk lobby was especially powerful, Johnson announced his administration would step up its efforts to bolster milk prices. Johnson withdrew his candidacy just 10 days later, but the milk lobby had already begun buttering up Humphrey.

The Milk Producers contributed $90,000 to Humphrey's presidential campaign. The money came entirely out of corporate funds - which is illegal - and much of it flowed through secret channels.

A handful of years later, these Democrats would cry wolf at Nixon's blatant corruption, but critics of the day were waved off.

"Frankly, I think they're wrong," former Humphrey aid Ted Van Dyk said to the Washington Post. "Otherwise, every lawyer and consultant in Washington is going to be out of business. They're all paid out of corporate funds."

When Nixon won the 1968 election over Humphrey, the milk lobby cut their losses and turned their attention to the victors. One of former President Johnson's lawyers handed over the dollars.

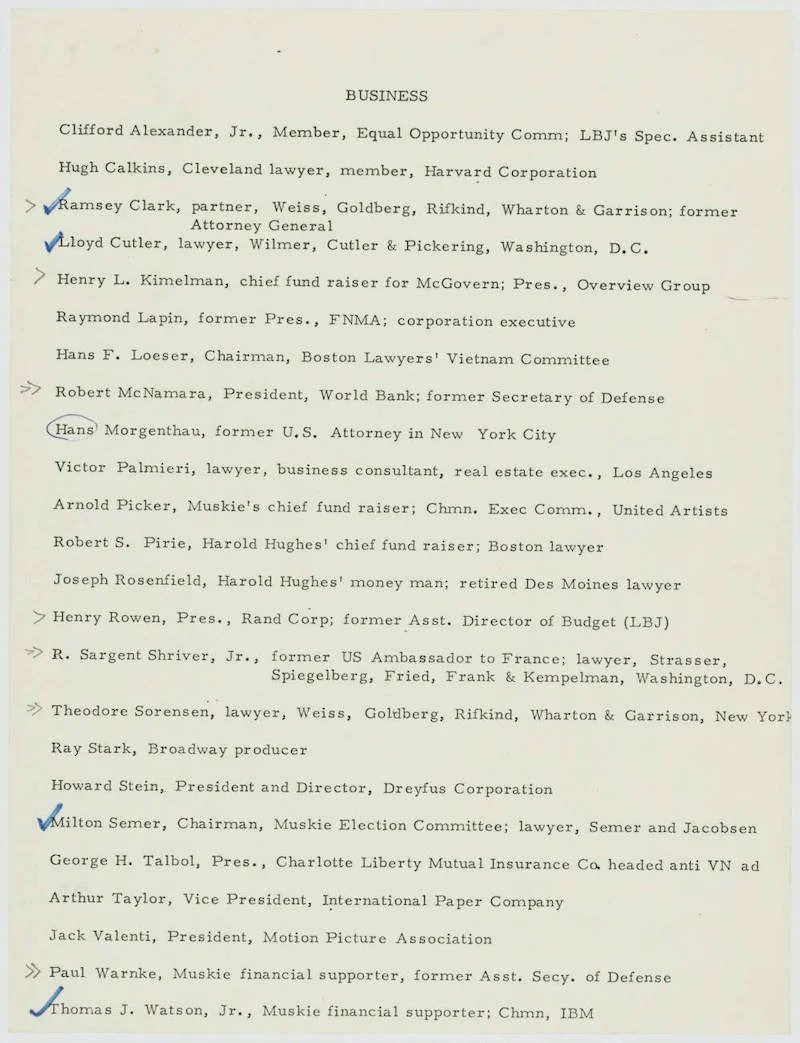

Milton Semer lost his job as a top White House lawyer after the election, but the milk lobby was quick to find him work. Semer, whose name would later appear on Nixon's personal list of enemies, was tapped as the bag man for a $100,000 cash exchange. He flew to California with one thousand $100 bills and handed them over to Nixon's personal lawyer.

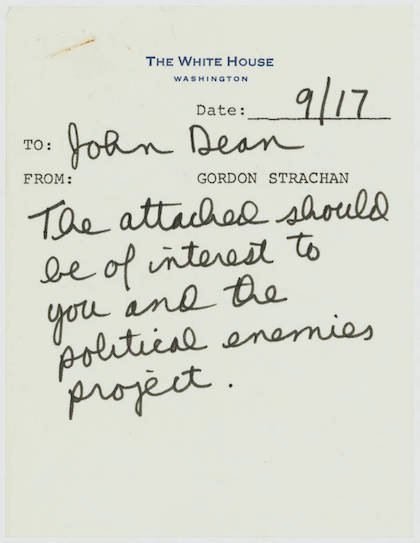

A page from Nixon’s enemies list.

It came as something of a peace offering, as the milk lobby looked to purchase a sympathetic ear in the White House. Semer may not have known it at the time, but he opened a Pandora's Box. Just a few months later, the Nixon Administration announced a historic increase in milk price supports. The milk industry responded, bankrolling Republican campaigns for Senate, where they won a majority in 1970.

Nixon's and the Republican Party's power was on the rise. At least in part, they had the milk industry's dirty money to thank for it.

IT'S ALL IN THE HEAD

They had engineered a political revolution.

Conservative Republicans were poised to win over white voters in 1972 by capitalizing on racist anxieties around public school integration and Black activism. It yielded monumental gains for the southern Republicans, where they were finding electoral success for the first time. Nixon and his strategists saw the dairy industry as another tool to beat the liberals.

So they agreed to take another $2 million in dark money from the Associated Milk Producers to spend on the campaign. In return, a federal government guarantee to the tune of about $100 million to fix the price of milk and impose tighter restrictions on imports. It was no economic rescue package either. According to USDA data, the US increased milk exports sixfold the following year. Milking public funds and White House connections proved a better return on investment than anything they could get out of a cow.

When the deal was done, Nixon rambled to the Milk Producers about his own marketing idea to boost milk sales.

"If you get people thinking that a glass of milk is going to make them sleep, I mean, it'll do just as well as a sleeping pill," he said. "It's all in the head."

They wanted to talk about how the money would be delivered, but Nixon interrupted.

"Don't say that while I'm sitting here." It is unclear if he was joking at this moment. "Matter of fact, the room's not tapped. Forgot to do that."

Everyone laughed. Probably only Nixon knew the room was, in fact, tapped.

"I don't want to go over the economics of it," Treasury Secretary Connally said.

"How about the politics?" Nixon said.

"Looking to '72," Connally said, "you're going to have to be strong in rural America."

On the same day, Nixon's Agriculture Department would announce an unprecedented increase in milk price supports. Later that night in a Washington D.C. hotel, a Milk Producers lawyer and Nixon's personal lawyer worked out the $2-million secret transfer.

SETTLED AND ACQUITTED

It all came apart in a different Washington D.C. hotel.

A group of burglars had been caught breaking into the Watergate, where the Democratic National Committee was headquartered. The investigation it tipped off would unravel the Nixon presidency, exposing the secret funds, the enemies lists, the dirty tricks.

The Watergate Hotel

Before his presidency was over, Nixon's Justice Department would investigate and file suit against the Milk Producers, much to his chagrin. Their once-shady payouts were gaining too much attention to ignore. That suit would later be settled the month Nixon resigned.

Treasury Secretary Connally would be charged with accepting an illegal $10,000 contribution from the milk producers. He was later acquitted.

Most of this is only known because of the obsessive paranoia that drove Nixon to bug and record so much of what went on in the White House. It offered a crucial window into the dairy industry's corrupt push for influence and a revenue guarantee. The record of this effort fades after Nixon's resignation and the closure of the Watergate investigations. It is clear at times he and his cronies thought they were the ones getting away with something. More accurately, his White House represented the culmination of a sustained effort by the milk industry to embed itself into the government's pockets deep enough to guarantee they would make a certain amount of money. A couple duffel bags of cash was a small price to pay for that.

Nixon resigned from the presidency in August of 1974 amid the scandals the botched Watergate break-in exposed. The details regarding the Vietnam War, the weaponization of the government against personal enemies, and the horribly offensive demeanor within the halls of power would all overshadow the comparatively boring story of the dairy industry's unsavory cash-for-support scheme. However, before the more salacious details came to light, special prosecutors issued subpoenas to the White House for tapes that could prove officials sold government positions and influence. The suspected buyers: campaign financiers, crooked lawyers and dairy lobbyists.

The beleaguered president's last day in the White House included a modest American lunch on a silver platter. Pineapple slices, cottage cheese, and a tall glass of milk.

###

This article's ingredients

Anatomy of a Scandal: The Milk Fund

By George Lardner, Jr.

Published in a November 1974 edition of Reader's Digest

http://jfk.hood.edu/Collection/Weisberg-Watergate%20Files/Dairy/Dairy%20102.pdf

Nelson Exhibit No. 12

Letter from the Law Offices of Reeves and Harrison to Harold S. Nelson

June 29, 1971

https://www.maryferrell.org/showDoc.html?docId=145095#relPageId=349

IRS Claims Milk Co-op Owes $16 Million

By George Lardner, Jr.

The Washington Post

April 14, 1976

Nixon's Fateful Reversal

By George Lardner, Jr. and Walter Pincus

The Washington Post

October 29, 1997

White House memorandum for John Dean from Charles Colson

September 9, 1971

"I have checked in blue those to whom…"

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Library, Southern Historical Collection

Rufus Edmisten Papers, collection number: 05528

https://finding-aids.lib.unc.edu/05528/#separatedfolder_75#1

President Nixon: Alone in the White House

By Richard Reeves

Published by Simon & Schuster, 2001

"Whoever is President of the United States…" (p. 308)

"Better get a glass of milk…" (p. 309)

"Tapes and documents related to…" (p 607)

https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/u3781439

Courage and Hesitation

By Allen Drury

Published by Doubleday, 1971

"Whoever is President of the United States…"

https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/u548656

History of Federal Dairy Programs

By Dr. Scott Brown

April 13-15, 2010

University of Missouri Food and Agricultural Policy Research Institute

https://www.fsa.usda.gov/Internet/FSA_File/1_2_overview_brown.pdf

Watergate: Chronology of a Crisis

Published by Congressional Quarterly, 1975

P. 159, 186, 259

https://search.lib.virginia.edu/sources/uva_library/items/u469849

The Sad, Stately Photo of Nixon's Resignation Lunch

By Dan Charles

NPR

July 16, 2015

Food Availability Data System: Dairy Products data set

US Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service

https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/food-availability-per-capita-data-system/